Citizen Science: Tips For Turning Everyday Outdoor Moments Into Meaningful Scientific Research

Did you know you could contribute to scientific discovery without a Ph.D? In fact, all you really need is a curious mind, and maybe a good pair of boots. Citizen science is the practice of everyday people contributing data to real scientific research, whether by snapping photos, logging wildlife sightings, or tagging species in trail cam footage. It's become an essential tool for researchers who can't be everywhere at once, and the data collected by volunteers is helping to track species migrations, monitor climate impacts, and even shape conservation policy.

And here's the best part: If you already spend your weekends hiking, paddling, birdwatching, or just poking around in the garden, there's an excellent chance you're already sitting on a treasure trove of valuable data. With just a bit of intention — and maybe an app or two — you can turn your favorite outdoor pastimes into meaningful contributions to science. Your favorite breathtaking campsite? It could be home to a rare frog. The bees in your backyard? They might help fill in the blanks on pollinator health across the continent.

At a time when ecosystems are under growing pressure, this kind of grassroots data collection isn't just helpful, it's mission-critical. Every data point you contribute brings scientists one step closer to understanding how to protect the natural world. And in doing so, you're helping ensure that the landscapes you love — the forests, coastlines, meadows, and mountains — remain wild, thriving, and full of wonder for generations to come.

Snap a photo of a plant or animal

Across the world, ecosystems are shifting in ways that often go unnoticed. Climate change, urban development, and habitat loss are pushing species into new territories, or out of their native ranges altogether. While scientists work to understand these shifts, the sheer scale of the natural world makes it impossible for professionals alone to monitor what's happening in real time. But believe it or not, what's missing isn't necessarily equipment or funding. It's eyes on the ground.

By crowdsourcing observations of plants, animals, fungi, and more, iNaturalist solves this specific problem. It gives scientists access to millions of geotagged photos that help map species ranges, monitor rare sightings, and detect invasive threats. For instance, thanks to data shared on iNaturalist, scientists were able to document the range contraction of the jaguarundi, a South American wild cat once found further north than it is today. Another user's upload led to the first North American sighting of the invasive elm zigzag sawfly, triggering a fast response from Canadian authorities.

Every time you snap a photo of a flower, bug, or bird and share it on iNaturalist, you're contributing to this massive, open-access scientific effort. Your observations help researchers track biodiversity in real time, fill in data gaps, and respond faster to ecological change. And because even common species matter, your photo might be the puzzle piece that completes a much larger picture.

Record bird calls with an ID app

Birds are some of the most visible and vulnerable creatures in the natural world. Since 1970, North America alone has lost nearly 3 billion birds across hundreds of species. Migration routes are shifting. Populations are declining. While scientists scramble to understand what's driving these losses, one major obstacle remains: They simply can't be everywhere at once. Monitoring these changes across vast distances requires eyes and ears. Lots of them.

And that's exactly why they've come to depend on platforms like eBird. Built by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and managed by Avian Knowledge Northwest, eBird turns birdwatching into a powerful global science tool. Users submit sightings and recordings that feed into one of the largest biodiversity databases in the world. This information has shaped conservation policy, informed endangered species listings, and helped protect critical habitats. When the Red Knot, a long-distance migratory shorebird, faced dramatic population crashes, it was eBird data that helped fill in the missing pieces — tracking the bird's 20,000-mile journey and supporting its listing as a threatened subspecies under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

So if you've ever paused to admire a bird, you're already halfway there. By using eBird — or pairing it with the Merlin Bird ID app to help identify calls — you can turn everyday birdwatching into something far bigger. Your observations, whether in your backyard, on the trail, or at your favorite birding spots, help scientists map migration patterns, track species health, and prioritize conservation. What seems small to you might be the data that saves a species.

Take note of seasonal changes

Nature has long followed a rhythm: Flowers bloom, trees unfurl new leaves, birds arrive, and the seasons cycle on. But as the climate warms, spring often arrives early, fall lingers longer, and the natural cues that plants and animals rely on start to misalign. Basically, nature's rhythm is changing. As a result, pollinators show up too late, and insects hatch too soon. These shifts may seem subtle, but they ripple through entire ecosystems, disrupting everything from food webs to migration routes.

The USA National Phenology Network (USA-NPN) is helping scientists make sense of these changes. Through a program called Nature's Notebook, volunteers across the country track when plants leaf out, flowers bloom, and animals appear. This growing database (phenology is the study of seasonal change markers) powers everything from climate change models to invasive species forecasts. The network's spring indices are even used by the EPA and National Park Service to assess ecosystem health and guide seasonal planning. For instance, in Saguaro National Park, managers have used this data to control invasive buffelgrass. And in New York, it's helped time efforts to manage tree-killing pests like the hemlock woolly adelgid, a destructive insect from East Asia.

You don't need special training to contribute either, just curiosity and a willingness to look closely. By logging something as simple as the first tulip in your yard or the color change in a maple tree, you're helping build one of the most important climate data records enthusiasts have. Each observation becomes part of a bigger picture, one that's helping scientists, land managers, and conservationists protect ecosystems in real time.

Record frog or toad calls near water

Frogs and toads may be small, but they're some of the loudest voices in the natural world, until they're not. Amphibians are disappearing at an alarming rate due to pollution, habitat loss, disease, and climate change. With over 2,000 species globally threatened, scientists are sounding the alarm. Because amphibians are sensitive to environmental change, their silence is often the first sign something in the ecosystem has gone wrong.

FrogWatch USA helps fill critical data gaps by enlisting volunteers to monitor frog and toad populations through sound. Participants are trained to identify species-specific calls and record them at local wetlands throughout the breeding season. This data, submitted to a national database, helps scientists and land managers track population trends, detect invasive species, and monitor the health of fragile wetland ecosystems. In some areas, volunteers have even documented new species appearances, influencing conservation decisions like habitat restoration and invasive plant removal.

It's also worth mentioning that you don't need to see a frog to make a difference: You just need to listen. By joining FrogWatch, you can turn peaceful evenings near a pond or stream into powerful scientific contributions. Each call you record becomes part of a growing dataset that helps researchers understand where amphibians are thriving, where they're in trouble, and how people can protect them before it's too late.

Log your litter pickups

Plastic pollution isn't just a beach problem. It starts on sidewalks, trails, riverbanks, and backroads, slowly working its way to streams and oceans. From cigarette butts and bottle caps to food wrappers and fishing line, this litter endangers wildlife, damages ecosystems, and clogs up waterways. But to truly fight pollution, you need more than good intentions – you need data. Without knowing what kinds of trash are out there and where it's coming from, solving the problem becomes a guessing game.

Thankfully, there are platforms like Marine Debris Tracker, which turns everyday cleanup into powerful, location-based science. Developed by the University of Georgia and NOAA, this free app lets volunteers log individual pieces of litter, from plastic bags to microtrash, then submit them to a global, open-access database. That data helps scientists understand how litter moves, measures the effectiveness of policies, and targets specific pollution sources. Even along the Ganges River, community tracking revealed how socioeconomic factors shape what ends up on the ground.

If you've ever picked up trash on a hike, a beach, or a city sidewalk, you're already doing the work. Marine Debris Tracker just helps it go further. By logging what you collect, you're not just cleaning up your neighborhood. You're contributing to global research, policy change, and long-term solutions. And each time, you contribute real data for real impact.

Report strange or rare wildlife behavior

Nature tends to follow patterns, but every now and then, something breaks the mold: A bird singing out of season; a sick-looking deer lingering near a trail; an animal showing up far outside its usual range. These moments might seem like quirks, but to scientists, they can be early clues that something's off in the ecosystem. Detecting those clues early can make a critical difference in how researchers respond, and how quickly they can intervene to protect vulnerable species or habitats.

iNaturalist isn't just a tool for logging everyday sightings: It's also a place to document the unexpected. Whether you're reporting sightings of a rare species, out-of-place wildlife, or signs of disease, these outliers can help researchers monitor emerging threats and ecological disruptions. From there, conservation agencies and researchers often monitor unusual sightings for signs of invasive species, habitat degradation, or wildlife health issues. In some cases, these odd reports have even led to new research projects or conservation interventions.

So if something seems strange on your next hike, don't brush it off — log it. Uploading a photo, video, or note through iNaturalist could alert scientists to patterns they would otherwise miss. You don't need a degree to make a difference, just your curiosity and a smartphone. The more people reporting the odd and unusual, the stronger the collective ability becomes to spot trouble before it spreads.

Upload photos of glaciers or snowy areas

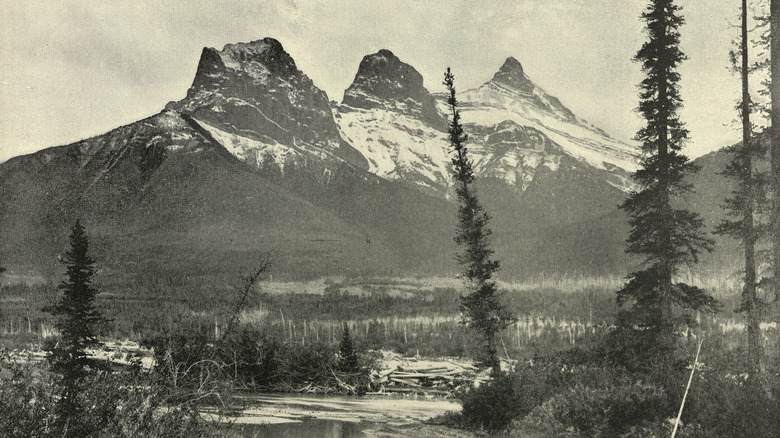

A hundred years ago, surveyors hauled cameras up mountain peaks to capture black-and-white snapshots of the Canadian wilderness. They couldn't have known that their glass plate negatives would one day help scientists track the effects of climate change. But thanks to the Mountain Legacy Project, those historic images now serve as benchmarks, revealing the retreat of glaciers, the upward creep of treelines, and how fire has reshaped entire ecosystems over time.

Today, modern hikers and outdoor lovers can pick up where those early surveyors left off. The Mountain Legacy Project invites citizen scientists to photograph those same landscapes and compare them with century-old views. These "image pairs" become powerful visual records of environmental change. Records that land managers, ecologists, and Indigenous communities use to understand what's shifting, why it matters, and how to respond. In one case, repeated photos of the Kaskawulsh Glacier captured a retreat so drastic it redirected an entire river.

If you're out in the mountains and snap a shot of a glacier, snowfield, or alpine ridge, it could contribute to this growing visual archive. Even a casual photo can become a scientific tool — especially if it's taken from a known viewpoint or includes recognizable landmarks. It's a simple way to plan out your next hike so it counts for more than just the memories.

Track pollinators in your garden

Backyard gardens might seem far removed from the frontlines of conservation, but for pollinators like bumblebees, it's vital buzzing ground. Across North America, native bee populations are in decline, threatened by habitat loss, pesticide use, disease, and climate change. The trouble is, their disappearance isn't just a pollination problem, it's a biodiversity crisis. Yet despite their importance, there are still major gaps in what scientists know about where bumblebees are thriving or disappearing.

One citizen science project empowers everyday people to photograph and upload sightings of bumblebees, which are then verified by experts and logged into a continental database. That project is called Bumble Bee Watch, (entomologists tend to prefer "bumble bee" written as two words) and the observations they compile help scientists track species distribution, locate rare or endangered populations, and even guide habitat restoration efforts. The data has already contributed to major conservation wins from identifying persistent populations of species once thought lost, to guiding policy decisions and formal species assessments.

All it takes is a smartphone, a little curiosity, and a few minutes outdoors. Whether you're tending a backyard flower bed or spotting bees at a city park, your photos can make a real scientific impact. By participating in Bumble Bee Watch, you become part of a growing network of community scientists helping to map pollinator health and distribution across the continent. It's a small act that connects your garden to a continent-wide conservation movement — especially if it's a garden designed to attract amazing pollinators.

Tag species in trail cam footage

It's easy to imagine wildlife research happening deep in the backcountry, but much of these days is remote, dependent on sorting through mountains of trail cam footage and audio recordings. Researchers use these tools to monitor animal activity, track migration routes, and study how species respond to environmental changes. But there's far more data than they can analyze alone. Without help, some footage might never be seen, and key signs of change could go unnoticed. That's where citizen scientists come in.

Zooniverse, the world's largest platform for citizen science, makes it easy to help. You can identify animals in trail cam images from places like the Serengeti or the American prairie, tag penguins in remote Antarctic colonies, or even track the movement of deer and coyotes in North American forests. Projects span parks, preserves, and wildlands around the globe, and all they need is your eye for detail.

It's a small action with big consequences. Every image you tag helps scientists spot patterns, track species, and respond to change — the same kind of insights that help protect the trails, parks, and wildlife you already care about. Best of all, you can contribute anytime, from anywhere. Whether you're sipping coffee at home, waiting your turn at an appointment, or winding down after a hike, your clicks become part of something much bigger.

Join a local bioblitz

Even the most seasoned nature-lovers can walk a trail without realizing just how much information they're passing up. Each tree, insect, bird call, or unfamiliar plant offers a snapshot of the ecosystem. But without anyone recording it, that moment disappears. Multiply that by thousands or millions of parks, forests, and backyards, and the result is a massive blind spot in society's collective understanding of local biodiversity.

For those interested in contributing, there are many ways to dip your toes into citizen science. But arguably, one of the best just might be a bioblitz. These short, high-energy events rally everyday people to identify and log as many species as possible in a defined area over the course of a single day. Participants photograph wildlife using platforms like iNaturalist, while expert scientists help with IDs and guide the process. For outdoor enthusiasts, they're part scavenger hunt, part field class, part conservation mission. And they produce real data that land managers use to track invasive species in national parks and elsewhere, guide habitat restoration, and monitor ecological change.

If you're curious where to find one near you, SciStarter is the place to start. It's a central hub for citizen science projects, including bioblitzes and a wide range of other initiatives. Whether you want to document amphibians, count clouds, or analyze microbes in your neighborhood pond, SciStarter connects you with hands-on science experiences tailored to your interests and location. And the best part? It's lab coat-optional.